Doug loved to travel.

When we met, he had never been on an airplane, but that did not last long. Doug has crisscrossed the United States and traveled abroad time and again. Travel became his jam. He enjoyed everything about it and every mode of transportation, car, boat, plane, and train. Doug capitalized on the planning, the packing, the anticipating, the turbulence, the distance, the crowds, the coffee stops, and the aisle seats—all in the name of adventuring.

Airplane travel was exhilarating and simultaneously unpleasant for him. Doug is a tall man; an aisle seat, a Starbucks double shot, and boarding last were his flight signatures. He was enamored by how quickly a plane took him from point A to point B anywhere in the world. Concurrently though, the overhead bins were a forehead smack hazard, the seat in front of him sausaged his knees into his hip sockets, and his feet were robbed of their assigned floor space by the “personal item.” But none of that slowed down his unceasing travel bug.

Doug delighted in planning the adventures almost as much as he enjoyed the quest. He made most of the travel arraignments, from transportation to hotel stays to all the fun we experienced while there. He liked scouring deals and talking to people (or buying books) about the must-see attractions. The family trips that included the kids were his favorite.

Dementia creeps in slowly, lurking in the dark shadows of silence like growing mold behind damp sheetrock. Years can pass while compensation veils brain change. One afternoon Doug asked me to double-check a trip reservation he had made. The oddness of this request struck me. Rarely did he invite verification. Doug brushed it off as tired. But I cataloged it with the misplaced keys, TV remote challenges, blank looks of confusion, and repetitive questions. These oddities were becoming a mounting pile of mishaps tucked into our relationship’s fearful, inaudible shadows, and they were starting to smell moldy. I knew something wasn’t right.

TSA offers a Pre-check flight option for a fee. We signed up. I figured simplifying the airline boarding process was always worth it. Doug liked the faster lines; I liked that he didn’t have to take off his shoes or his belt; for some reason, getting them back on was complicated. In crowded airports, we held hands so we would not get separated. Doug got turned around, reentering the gate hurried traveler frenzy after using the bathroom. I didn’t see him come out; we lost each other.

Panic is hard to breathe or think through. It clutches and squeezes, and beads of sweat form. We found each other eventually. Doug had a sweaty brow, and I needed to sit down. Pre-diagnosis is consumed with suspicions, anxiety, and deferments. You don’t know what to call it, but you know something’s amiss. We were both compensating, doing our best to deny any incongruities. Eventually, brain change wins and gets a name. That day brought regretful relief.

The pandemic kept me from traveling. Dementia keeps Doug from traveling. His brain change is beyond pressurized independence and crowds. Peace, quiet, familiarity, routine, naps, and a big white dog now control Doug’s days, a far cry from airport existence. Buckling his seatbelt in the car proves troubling enough.

I recently folded the map and traveled to Florida. A new grandbaby boy, sharing part of my husband’s name, gave me the nerve to leave and love. I started preparing for the trip two months prior. Doug’s caregiver, Kathy, was involved, and so were my kids and brothers.

Planning to be nearly 3000 miles east for 6 days, leaving Doug at home is not a relaxed pursuit. It started with a night away, a practice for me, Doug, and Kathy. That single night at a local hotel by myself deserves its own blog. In short, it was quiet, I was lonely, and later my widow friend, with vast compassion and a ready hug, said, “get used to it; there will be more quiet, lonely nights in your future.” I don’t know what I expected when I walked in the door after that first overnight away from Doug in years, but he did not miss me. Or at least he did not express missing me. The dog did, though.

Kathy and I decided longer than one night away needed to be the next step in this practice process. Routine is Doug-with-dementia’s closest companion. Nights are wrapped in it from dinnertime forward. Kathy is with Doug on weekdays; I cover nights and weekends. Kathy slept over when I traveled; she and Doug needed practice. They needed to find their nighttime rhythm together. There is the dinnertime routine, the TV time routine, the bedtime preparation routine-changing clothes, brushing teeth, washing up-all requiring hands-on assistance, and the overnight routine, which only sometimes includes restful sleep.

I could not get my head around two nights away in a quiet, lonely hotel, so I drove three hours to my daughter’s house instead. This second practice was way more fun. I treated my sister-in-law to a birthday dinner with cake, and I relished in grandchildren, pastries, free time, and the sun. The two-night, three-day practice flew by, and suddenly I was home. This time Doug lit up when I walked in the door. Maybe he missed me. The dog did, for sure.

After the two-night practice, I bought a plane ticket to officially fold the map. We had more than a month to prepare. I told Doug about the upcoming trip. With an opaque, nearly transparent expression, he said, “Okay.” I told him he was not coming with me, and with Garfield-the-cat indifference, he replied, “Okay.” I planned his days with family visits and outings. I precooked meals and went over Doug’s many routines with Kathy. Then, less than a week before takeoff, Doug got an upper respiratory infection, and we visited the ER in fear of pneumonia.

The trip stayed on schedule with the addition of cough medicine and some extra attention. I cried nervous grief-filled tears on my way to the airport. I missed Doug as the tour director, bringing energetic anticipation to the adventure. I missed him as my husband and as the father and grandfather to our Floridian family. I missed him as my friend. I felt alone. The airports were shoulder-to-shoulder crowded with long lines not suitable for advanced dementia. I was relieved Doug wasn’t with me. TSA Precheck was no faster than regular check-in. By the time I boarded, I was ready for a nap.

Florida and family were fun in every way. I look forward to going back. When I arrived home late evening, Doug was still awake, entirely out of routine. I walked in the door, and he looked at me, clad in his familiar nighttime tee-shirt and navy cotton pajama pants, and said, “I missed you,” he leaned in for a hug, and I choked back tears and said, “I missed you too.”

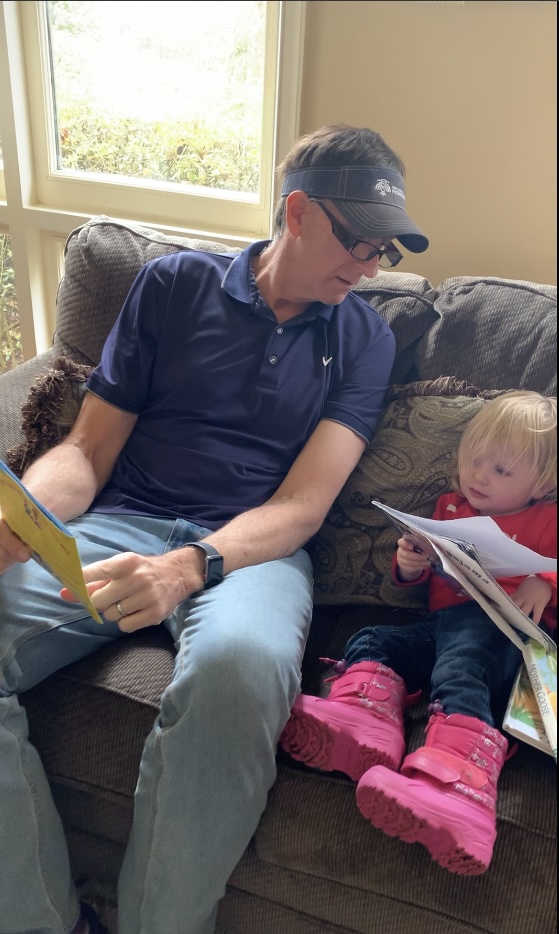

Eventually, dementia speaks up with little regard for the surroundings. Its seeping moldy seams expose the decay brewing in the dark. Doug is past traveling for fun. He’s past traveling, except for short distances that don’t require significant routine interruptions and crowded chaos. We live content with less doing and more being. Daily I wait for the lucid interactions and smiles that still beautifully bloom through his dementia-mildewed persona. Doug’s timid hugs and sober epochs of recognition and appreciation, more than our itinerant adventuring ever did, keep me anticipating and looking forward one day at a time.

Karen