Dementia is a slow, persistent, odd mixture of impaired undoing and living.

Doug and coffee were synonymous! There was even a time he momentarily romanticized he could be a coffee connoisseur. He took his coffee seriously and took people to enjoy a cup before going to coffee was a thing. Doug even worked a very short stent at Starbucks, but that’s a different story for another day.

We had a fancy coffee maker, a bean grinder, and a French Press. Doug loved his morning brew routine, enjoyed a coffee break in the afternoon, and always looked forward to sharing a cup with a friend at the newest up-and-coming (or hole-in-the-wall) coffee shop.

He insisted that making a good cup of coffee is a delicate, sophisticated process. First, he would say, it involved grinding the beans to the ideal texture for the expert smooth taste. Then it required using the correct amount of water (filtered if possible) at the appropriate temperature. And finally, after completing the brewing process to perfection, which I guess is a thing all by itself (Doug would say this is when you can ruin all deliciousness), a good morning aromatic sip necessitated the right coffee mug. So, Doug collected assorted mugs from his many travels, each with its own story.

Dementia has undone Doug’s ability to make coffee and care about it. This reversing wasn’t sudden or abrupt, like an epiphany or a surprise. Instead, it happened slowly, in steps, in phases, as if his coffee knowledge and passion gradually leaked out and evaporated into unlearning.

At first, he struggled with the order of the steps he used, but he muddled through, sometimes remembering and making coffee seamlessly, and other times baffled by the clunkiness of his ability. Then grinding the beans all by itself became problematic, so he occasionally purchased ground coffee beans to have in case the bean grinder was impossibly uncooperative. He eventually scrapped the fancy coffee maker and the bean grinder altogether and used the French Press exclusively. It was more straightforward, especially when using pre-ground beans and a hot water tap. But even that became unworkable eventually.

Doug is, most of the time, entirely apathetic about coffee now. The preparation has become too complicated, so he no longer makes it; I do. I use a simplistic coffee maker with pre-ground coffee beans, water, and a basic push-button start. I set his coffee at the breakfast table in what I think is a favorite mug. He doesn’t seem to care, sometimes he drinks it, and sometimes he doesn’t, but he always says thank you.

The early signs of Doug’s coffee confusion eluded me due to patchy inconsistencies. I would justify the confusion as tiredness or stress, not realizing brain change was well underway. I didn’t catch on until much later in the dementia process when the confusion became consistent and prominent enough that I could not miss it.

Since then, I have learned. I now know the dementia digression of any task always starts the same way. The slow, awkward undoing with a light bulb of coherency here and there is classic – two steps forward, one back, two steps forward, two back, two steps backward, one forward until backward eventually wins the war.

Doug’s executive functioning (step-by-step cognition) was where his early hiccups of dementia were first noticed, like in brewing coffee, keeping his golf score, driving a car, and playing cards. He is now in the later stage of the disease, meaning brain change is more global and simultaneously affects numerous regions. For example, the information his brain catches from his eyesight is progressively changing. I took him to an Ophthalmologist, thinking he needed glasses, but his vision was fine according to the eye tests; he did not need glasses. Still, he struggles with depth perception, peripheral vision, and even sometimes seeing what’s directly in front of him, like the spaghetti on his plate or the pillow on his bed. The parts of his brain that interpret his visual world are weakening, affecting many things like making the bed, eating a meal, buckling his seatbelt, or navigating up or down a curb.

Think about how you respond to what you see, trusting that your visual interpretation is accurate. Now consider how you would navigate your world if your brain did not accurately interpret what you see. It’s crazy confusing to consider Doug’s reality this way. Even crazier is his unawareness of the misinterpretations.

Dementia is a long slow road of persistent defeating brain change with intermittent coherent periods woven in, making much of it confusing and exhausting for both the person and the one helping. It is not like Doug does something without mistake one day, and the next day he is completely incapable. It’s more like this. Last year at this time, Doug made his bed religiously as he always did, every morning without a wrinkle; you could bounce a coin on it. But now, a year later, his bed-making skills are mostly absent. He still recognizes that the blanket goes on the bed, but the order – sheet, blanket, comforter, is a mystery, and smoothing one out over the other is abstract. Wrinkles and sometimes wads of bed covers are the best he can do, but every morning he still attempts to make his bed.

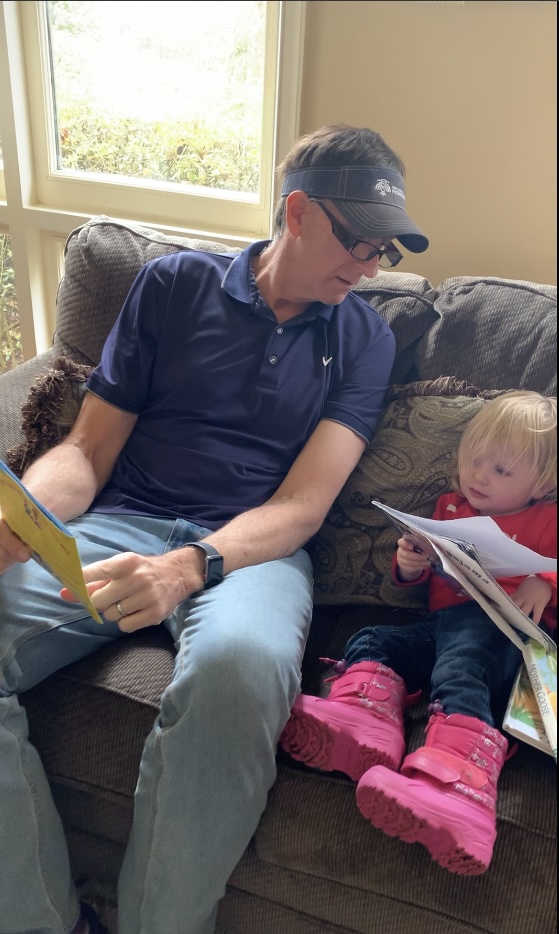

It’s strange what he does and what he no longer does, proficiently or even at all. He still laughs at a joke, whistles a little tune, and swings a golf club, but he struggles with most ADLs (Activities of Daily Living). I help him shower, brush his teeth, and get dressed. I hold his hand to cross the street, unbuckle and buckle his belt before and after the bathroom, drive him around, and serve him a plate of food at meals. Doug always used a handheld razor and shaving cream to shave. Then, a year ago, he started using an electric razor at my prompting. I figured it would be less risky for him and less complicated for me to manage. He has always been clean-shaven, never much for facial hair, but now he misses large splotchy spots and doesn’t notice. I imagine soon I will be stepping in as his shaving buddy.

Each area I assist with has gradually dissolved from competent proficiency to ineffective ability, with occasional lucidness within the disappearing. When lucidity brightens Doug, it is tempting to think he will get better and relearn, memorize, or reconstruct the details. It seduces me into believing that if I help a little more, clarify better, or ensure he gets adequate rest, exercise, broccoli, or fresh air, all will reverse and return to normal. But alas, it just isn’t so. The pain in my heart catches and stings afresh each time I realize lucidity is temporary and backward is pilfering new territory.

Cohabitating with dementia’s undoing reveals soggy and wishy-washy sentiments in me. It hovers grey and muted as my insides wrestle with loss while trying to reconcile what remains. Grieving the loss of someone who lives is painfully raw. Some days grief consumes me, but most days, joy and sorrow hold hands as we walk out fragile tension together.

Prayer helps me find my voice, and it empowers me forward. Doug and I believe life is sacred and time on earth, however short or long, is a priceless, God-given gift that includes an embedded assignment to spread love around. Doug still does that. Even with advanced dementia, he extends love to me, his family, friends, and even strangers. Indeed, his brain change is a slow, persistent undoing, and backward is taking additional territory daily. Still, Doug’s spirit is strong, and his display of love inspires me repeatedly, reminding me one day at a time that grief and love are intertwined.

Karen